On December 12th 2015, 195 countries signed the Paris Climate Agreement at the Conference of Parties in Paris. The goal is to keep the global average temperature rise to 2°C and to do everything possible to limit warming to 1.5°C.

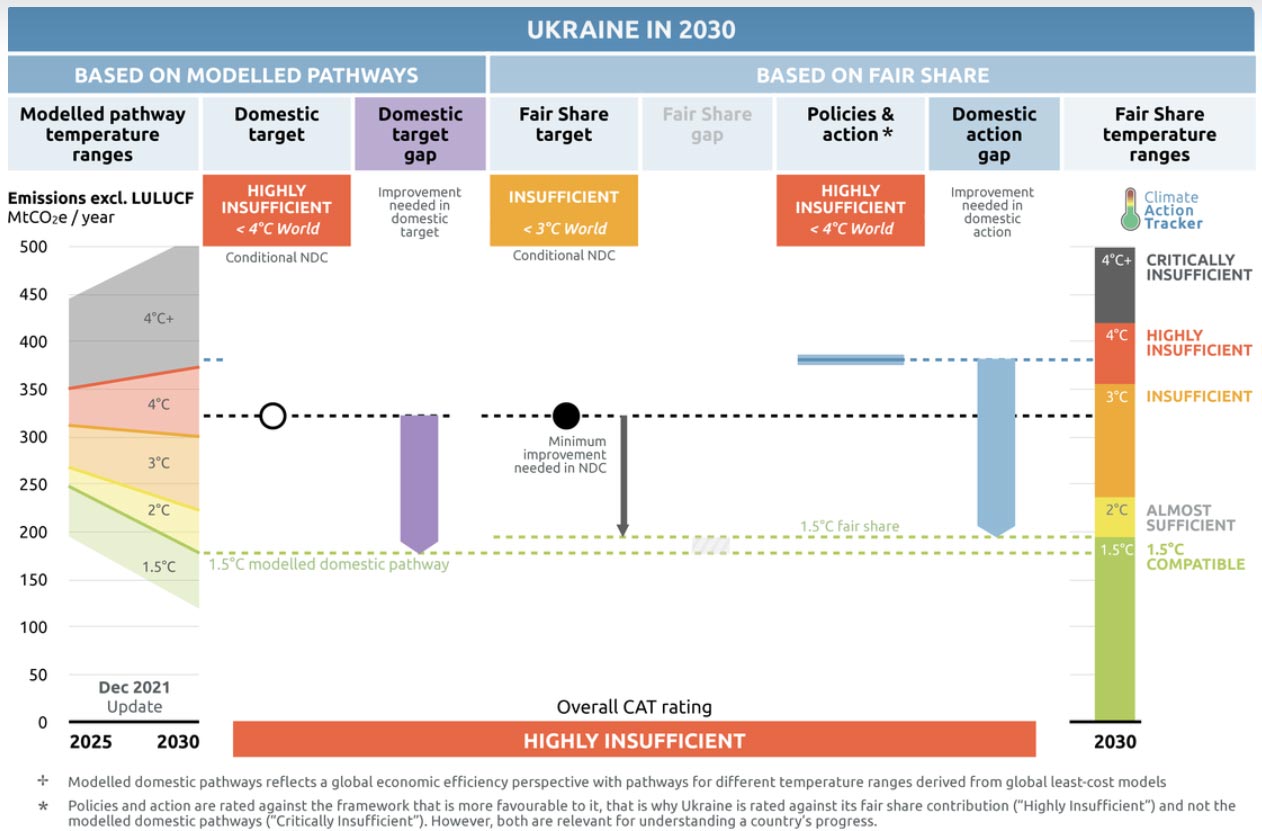

Under the Paris Agreement, every 5 years, countries have to adopt Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), and each new version of the document must be more ambitious than the previous one. Ukraine submitted its updated NDC on July 30, 2021. The new climate goal stipulates the need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 65% by 2030 compared to 1990.

In order to monitor the process of fulfilling the overall goal of the Paris Agreement, it has established a mechanism called Global Stocktake (hereinafter – GST). The process is organised in such a way that the signatory countries to the Paris Agreement submit reports on the status of their climate goals, and the Secretariat of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), together with experts, the public and scientists, analyses these reports. Already in 2015, countries, including Ukraine, agreed that by the end of 2023, all of them will go through this process to receive a report with conclusions and recommendations.

Data preparation and analysis have been going on for two years now, and during the recent Conference of the Parties in Bonn, the parties agreed on the structure of the GST. To be more precise, they almost agreed. In general, the structure was agreed upon, but since the UN makes decisions by consensus, as many as 4 different options were proposed for the section on climate action financing. The final version will be decided at the next COP28 conference in Dubai.

In fact, we are already realising that countries are not moving towards the ambitious goal of the Paris Agreement. How? Last year, the Secretariat of the UNFCCC presented a synthesis report analysing all climate commitments of countries. Also in March this year, the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) published its updated synthesis report. It highlighted how far off course the world is – even if everyone fulfils their commitments, temperatures will rise by around 2.5°C by the end of the century.

So how can the GST process be useful, especially for Ukraine?

During the UN climate talks, the parties usually argue to the bitter end over two topics: fossil fuel phase-out and finance. The main problem with finance is the dependence of countries vulnerable to climate disasters on grants and loans from richer countries. At the same time, rich countries are not ready to promise that they will cover all the financial needs of developing countries and avoid making any hard commitments on paper.

As for the phase out of fossil fuels, countries are not even ready to talk about such a necessity. Despite the fact that the burning of fossil fuels is the main cause of the rapid antropogenic climate change, the parties to the conference are avoiding commitments to phase out coal, oil and gas in every way possible. Last year, at COP27 in Egypt, governments failed to agree on this wording in the final document, as fossil fuel producing countries such as Saudi Arabia, Russia and Iran were against it.

In 2022, the world has already seen that dependence on coal, oil and gas equals energy insecurity, even if we ignore the impact on climate change. The global fossil fuel market has suffered a crisis due to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, as countries that used to be its customers have begun to actively develop renewable energy sources and energy efficiency. In this context, Ukraine has a chance to show itself as a country that, despite the war, understands the importance of climate action.

We know that the GST results will show that countries are not doing enough. However, the document will contain recommendations on how the parties to the Paris Agreement can get back on track. The advice is likely to include a more ambitious target for reducing greenhouse gas emissions through energy efficiency and the transition to renewable energy, achieving climate neutrality by 2050, and effective adaptation measures. That is why Ukraine has the opportunity to use these conclusions to approve a course for green recovery at the international level.

By 2025, countries will formulate their updated NDCs, which, as you remember, should be more ambitious than the previous ones. We hope that by this time, Ukraine will have started the process of green post-war recovery and become an example of resilience in the international climate arena.