Russian military attacks on Ukrainian power plants were the first real example of an event that was always considered a theoretical scenario.

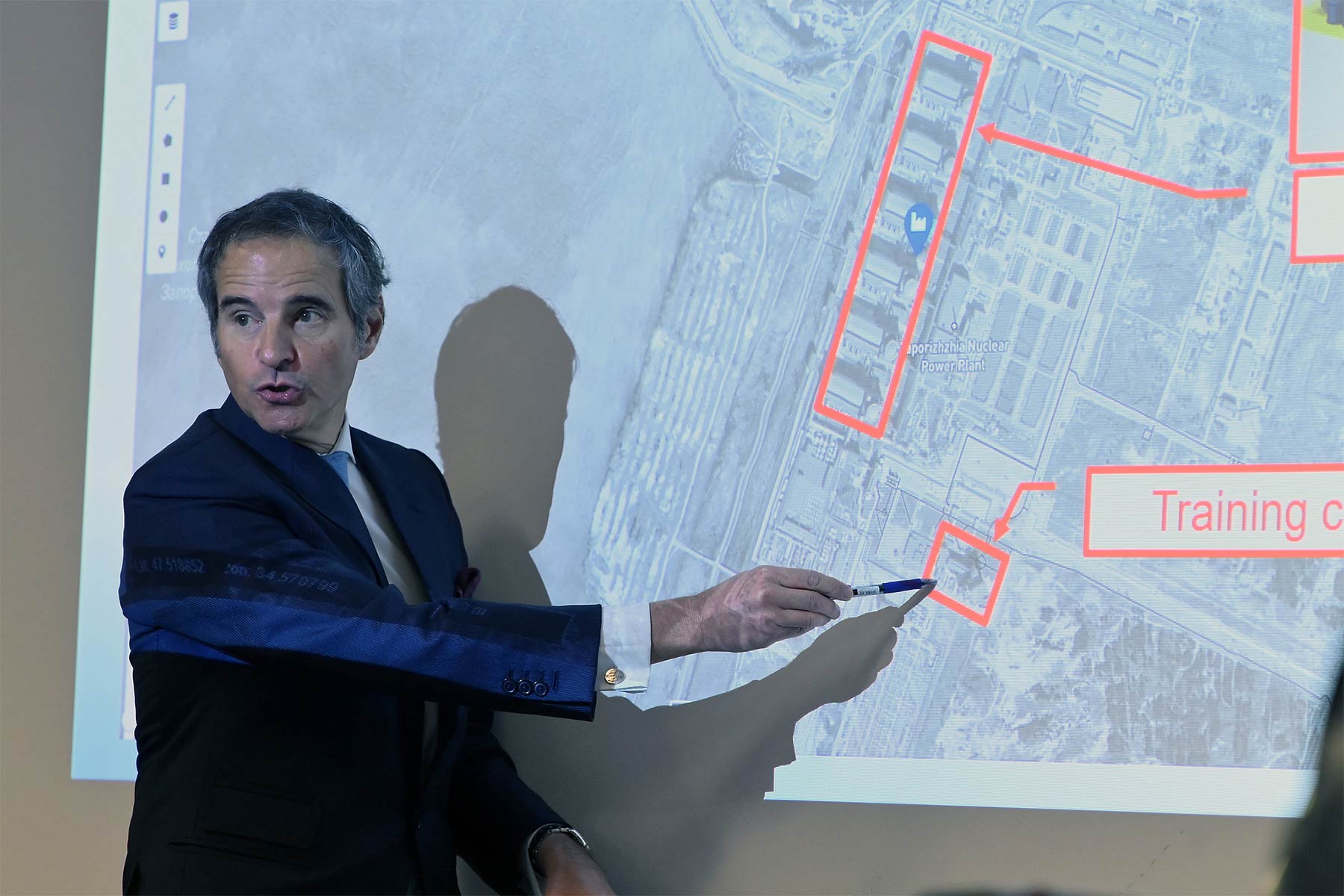

During the night of 4 March 2022, buildings at the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant in Ukraine were shelled by Russian tanks, resulting in a fire in the administrative building. Two of the three operating reactors were shut down. (The attack has been analyzed in detail by NPR.)

Earlier, on 24 February, the Russian army took control of the Chernobyl power plant site, entering the radioactive exclusion zone from Belarus and remaining there until 31 March. Fighting in the area led to a forest fire and destroyed a power line, raising concerns over the electricity supply to the complex of facilities that include spent-fuel cooling storage, three non-operational reactors, and the containment structure built above the reactor that was destroyed in the 1986 disaster.

Across Ukraine there were further incidents that led to nuclear safety concerns, as research reactors and radioactive waste storage sites were shelled. What would be a major concern in a normal situation was overshadowed by the high risk of an accident at Zaporizhzhia.

The possibility of military attack on nuclear facilities has been a matter of concern for many years. It is prohibited under the Geneva Convention and must therefore be treated as a war crime. Member states of the International Atomic Energy Agency IAEA have also approved a number of resolutions agreeing that attacks on nuclear facilities are unlawful and that member states will be ready to provide immediate peaceful assistance to the attacked party. It is not clear if IAEA member states have taken steps to approach Russia and express any formal concerns at the level of responsible bodies or calls for the withdrawal of troops.

The risk of military attack was regularly downplayed during the environmental impact assessments for the newly constructed reactors. The idea of a terrorist attack was seen as more realistic. Ukraine gained a clear appreciation of the risks during the war in 2014, when the Ukrainian army faced Russian attacks in the east of the country just a few hundred kilometers from Zaporizhzhia nuclear plant, posing the threat of deliberate or accidental missile strikes. In response, nuclear reactor operators and Ukrainian states took undisclosed steps to improve physical protection. However, it is now clear those steps were insufficient to protect the power plants.

Today, Russian military forces still occupy the site of Zaporizhzhia power plant, so the story is far from over. The plant is being used as a military base and is protected by mines laid on the river side. But operational reactors and spent nuclear fuel storage provide further protection, as it will be difficult for the Ukrainian army to shell Russian forces and risk an accident that could lead to long-term radioactive pollution or a major accident. The occupation of a nuclear power plant also gives Russian forces control over a significant proportion of Ukrainian electricity production. One unit on the site produces 5–10 per cent of the entire electricity produced in the country. (The latest reports state that two units are still producing electricity, but it is not clear if this is still the case and at what capacity they are operating).

The main fear is the uncontrolled release of radioactive materials into the atmosphere, which would clearly have serious health impacts and pollute large areas of land. There are various scenarios of what could go wrong and hence the scale of an accident. There could be a direct hit on a reactor building or spent nuclear fuel casks. This could happen with or without a major explosion. There is a possibility that if the external electricity supply is cut, nuclear fuel in the cooling pool or reactor core could overheat, melt, and release radioactive gases. For this scenario to occur it would only require that the site is disconnected from the grid supply until the backup generators run out of fuel.

These high-risk scenarios make accidents such as unauthorised movement of radioactive sources or destruction of monitoring systems less of a concern. As Russian military forces have now retreated from Chernobyl we feel some relief, despite them having looted expensive computers and laboratory equipment, results of scientific research and historical artifacts.

The idea of regarding existing nuclear plants as a potential weapon that has already been deployed on one’s territory has previously been considered. Having a nuclear site is effectively a military disadvantage for the country that is defending its territory. It serves as an attractive military target for controlling, but not destroying, electricity generation capacity. It provides a relatively safe base for an aggressor. It is also a site that defending forces are more likely to give up, rather than risk heavy fighting that could cause long-term damage to the area and your own people.

We have also seen that international agreements like those reached by the IAEA assume that no state would be willing to risk the lives of large numbers of civilians. The IAEA has found itself in a situation where observers have expected far more from the organisation than it could deliver. And it appears that member states have not done much to utilise common agreements to approach Russia with the call to stick to the agreement not to attack nuclear power plants.

The war in Ukraine has shown that nuclear power plants are attractive military targets. And that major wars are not a relic of the past. This is yet another reason to phase out nuclear energy. We can expect new initiatives to build new international agreements. But in times of war driven by unmet ambitions those agreements do not work.

Olexi Pasyuk,

Deputy Director,

Center for environmental initiatives ‘Ecoaction’

First was published at Acid Rains magazine